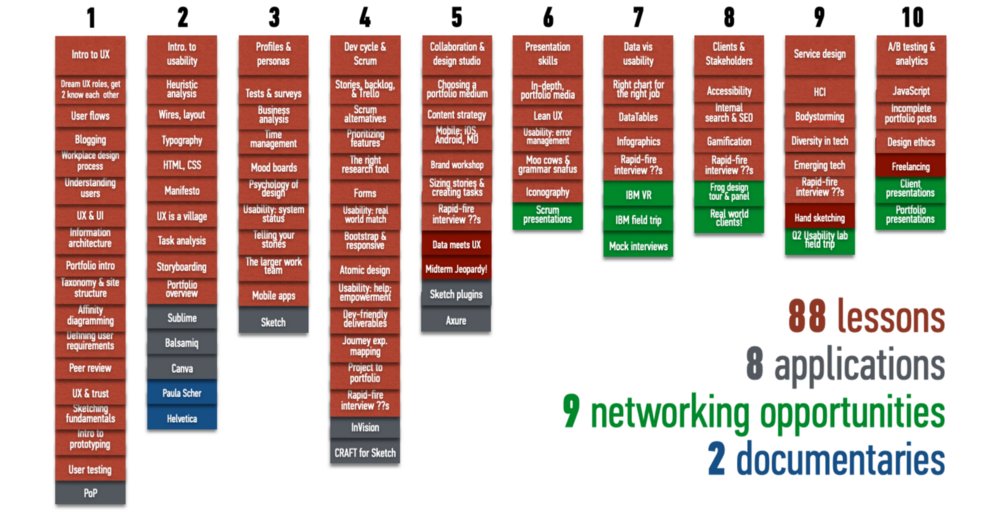

A syllabus from one of my UX classes; just the lesson titles are full of jargon! Each column is a week of lessons and events.

My ex-spouse, bless his heart, contributed some good to my life. (I can say this twenty years later, sixteen years into a marriage to the right partner. About the first one, all I can say is that every relationship sucks if it’s the wrong one, no matter how well-intentioned and good the people involved.)

Possibly the most important good he contributed to my tech career was this advice: “Jargon matters.”

Let me say that again, more loudly:

Jargon matters.

Everyone hates jargon, right? It’s used by some to exclude outsiders and preserve territory (lawyers and doctors, I’m looking at you!), or by others to show off being part of the “in” group at work. Sometimes it’s misused, and depending on the likability of the person making the mistake and the empathy of the observers, colleagues feel one of two excellent German concepts: Schadenfreude (pleasure in another’s misfortune) or Fremdschämen (embarrassment on someone else’s behalf).